Highlight

Heritage language research reveals the fragility of the 'mother tongue'

Achievement/Results

We think of our ‘mother tongue’ as if it is an essential part of who we are, which stays with us for life and shapes the way that we view the world. But our first language may not be as inalienable as we assume. New studies at the University of Maryland by Sunyoung Lee-Ellis and Shannon Hoerner are putting this assumption to the test, and their results suggest that some features of our mother tongue remain with us for life, while others are far more vulnerable to influences from other languages. These findings challenge long-standing views on the implasticity of human language abilities and suggest that the brain shows selective plasticity after initial language learning. Lee-Ellis & Hoerner are trainees in the program “Biological and Computational Foundations of Language Diversity,” which is supported by NSF’s Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeship (IGERT) program.

Lee-Ellis and Hoerner are learning about the resilience of the native language by studying heritage language speakers, a group whose language background provides a special window into the relative importance of the earliness and the amount of experience that a learner receives in different languages. Heritage language speakers are typically the children of immigrants who are exposed primarily to their heritage language when young and continue to use that language in the home, but who become more dominant in a second language later in life, due to their school or social environment. In the ‘melting pot’ society of the United States, heritage speakers have long made up a sizeable chunk of the population, but it is only recently that language researchers have recognized the special interest of this group. Heritage speakers are a unique group of bilinguals, since they are generally highly proficient in both languages, but are different from mono-lingual speakers of both languages. Lee-Ellis and Hoerner have been studying heritage speakers of Korean, one of the fastest growing groups of heritage speakers in the US today.

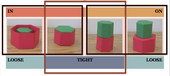

In their studies Lee-Ellis and Hoerner take advantage of the fact that different languages carve up the world around us into different categories. For example, Korean distinguishes two types of ‘s’ sound that English-speakers find it very hard to discriminate, and Korean speakers find it very difficult to tell the difference between nonsense words like ‘kasta’ and ‘kasuta’, something that is very easy for English speakers. Also, the two languages talk about spatial relations between objects in different ways: whereas English prepositions like ‘in’ and ‘on’ highlight the difference between configurations involving ‘containment’ and ‘support’, Korean speakers are more likely to classify the same configurations in terms of ‘tight fit’ and ‘loose fit’ (see the figure). Drawing upon research techniques from linguistics and psychology, the Maryland team found that Korean heritage speakers perceive speech sounds in a remarkably similar fashion to monolingual English speakers. That is, they struggle with Korean sound contrasts that they have been exposed to throughout their life, and succeed with English contrasts that are very difficult for their parents. In contrast, when Korean heritage speakers perceive spatial relations between objects they show the same bias as their parents to attend to the tight fit vs. loose fit distinction when viewing visual events. These findings hold much interest for our understanding of monolingual and bilingual language learning alike, and they show that some types of early experience have longer lasting impact than others. They are also valuable for teachers and parents who might be struggling to understand why children who are heritage speakers find it very easy to adapt to some aspects of their new language environment and much harder to adapt in others.

Address Goals

Discovery: the research investigates heritage language speakers, an important but understudied segment of the US population that holds great promise for understanding brain plasticity.

Learning: the research is the result of interdisciplinary graduate training that brings together students from different disciplines to carry out studies that they could not easily carry out individually.